HOUSE OF HAIRBALL

WHERE TEAPOTS AND TUNA BREATH LIVE IN HARMONY

The Diagnosis –

Monkeydo was so healthy until he wasn’t. In February 2018, at 11 years old, he began to vomit green. Often. Months earlier, Monkey would leave a deposit outside my bathroom door, hard and dry. I believe he was sending me a message even then that something was not right. I took him to a few vets. Good ones. X-rays and ultrasounds were done and showed fluid pockets between his stomach and liver, possibly hepatic cysts. Cytology indicated no cancer. So the treatment was a steroid shot, nausea meds and aspirating the greenish fluid as needed to keep him comfortable.

I spent hours researching liver cysts and befriended people in Arizona and Maryland whose cats also had hepatic cysts. Bob’s cat died before surgery could be scheduled. Lynn’s cat survived surgery at one of the best hospitals in Boston but died before a NY courier arrived with blood. I tracked down every morsel of information I could and discovered something important. Liver cysts were usually benign, harmless. So I relaxed a little.

When Monkey had a frantic episode during fluid extraction, crying out loudly and hyperventilating, I got scared. I switched vets and drove Monkey to a veterinarian specialist an hour away. She was highly recommended with credentials from UC Davis. But she admitted she had no experience with this. She attempted the fluid extraction using a sedative, but Monkey freaked out anyway. It was as if he knew it might kill him. The CT scan she ordered was perplexing. The report simply ruled out things. Monkey’s fluid pockets were now larger, obscuring the bile ducts and his gallbladder. The new internist suggested exploratory surgery and referred me to a board certified vet.

“Leakage into the abdomen would be the end of us.”

Dr. Ian Holsworth, the recommended surgeon, went through the CT scan images with me. It was the first time I had seen them. They revealed one huge, outer cyst and others that appeared to be inside the liver but attached to the large one. He called them pseudocysts because they contained bile. Then he said to me, “The trick is to remove the large cyst from the liver and seal it off without disturbing the others. They’re much like water-filled balloons and leakage into the abdomen would be the end of us.” I desperately wanted Monkey to be well, but this sounded daunting. I did not want to lose him during exploratory surgery with no assured outcome. Monkey’s symptoms were subsiding, and he seemed fine. I put off the surgery. But his protruding abdomen was a constant reminder of impending doom.

The Surgery –

In September 2020, the vomiting started again. Monkey could not keep anything down for several days. There were no appointments due to COVID-19, so I rushed him to the specialists where he was hospitalized. An ultrasound showed a large structure that was 5″ across and 2″ thick causing upper GI obstruction. And there were these new, tubular fingers of fluid. I phoned Dr. Holsworth hoping he was available. (He’s a teaching specialist and travels extensively.) He was in town. Monkey’s internist made the arrangements, scheduling Dr. Holsworth, his colleague, Dr. Campbell, and her own critical care team. They took chest x-rays, did new bloodwork and ordered Type A blood. The internist said it would be over $10K. I think she thought I might change my mind. I didn’t. I had postponed the first exploratory surgery ten months earlier, but now I had to face it. Moving beyond my fear was essential. But keeping Monkey alive was everything.

“The common bile duct was distended and filled with 6 cups of bile.”

Dr. Holsworth phoned me the evening of Monkey’s procedure. In his steadied Aussie accent, he asked, “If we see that nothing can be done, I need to know where you are on this.” I fought back tears and struggled to say, “If Monkey can’t be fixed, then I will be his very best friend and let him go.” I said the words, but they didn’t feel true. I hated that the pandemic prevented me from being there. When the surgical team called from the OR, they said there were no pseudocysts. Instead, Dr. Holsworth discovered that Monkey’s common bile duct was filled with 6 cups of bile. The tubular fingers they saw were his other bile ducts, swollen with fluid. Together, they had taken over the digestive role for his atrophied, non-functioning gallbladder. It explained why none of the images ever showed his biliary system. It was hidden behind these huge bile ducts which are normally the size of veins. The internist needed a decision. I felt Monkeydo deserved a chance and she agreed. Dr. Holsworth would downsize the stretched-out common bile duct and reattach it to the intestines. I gave the okay.

accent, he asked, “If we see that nothing can be done, I need to know where you are on this.” I fought back tears and struggled to say, “If Monkey can’t be fixed, then I will be his very best friend and let him go.” I said the words, but they didn’t feel true. I hated that the pandemic prevented me from being there. When the surgical team called from the OR, they said there were no pseudocysts. Instead, Dr. Holsworth discovered that Monkey’s common bile duct was filled with 6 cups of bile. The tubular fingers they saw were his other bile ducts, swollen with fluid. Together, they had taken over the digestive role for his atrophied, non-functioning gallbladder. It explained why none of the images ever showed his biliary system. It was hidden behind these huge bile ducts which are normally the size of veins. The internist needed a decision. I felt Monkeydo deserved a chance and she agreed. Dr. Holsworth would downsize the stretched-out common bile duct and reattach it to the intestines. I gave the okay.

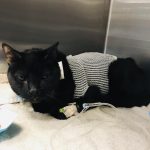

After five days in the hospital, I brought Monkey home with a feeding tube and several medications. The staples down his body looked like a giant zipper, and I hurt just looking at him. Recovery was rough on both of us. Thank God, the antibiotics and pain meds could be given via the esophagus tube. We became close friends with transdermal Gabapentin, Mirataz and Cerenia tablets. Monkey was often nauseous and hunched in discomfort before a BM. I felt his pain. But all I could do was just hold him.

We do not know why his bile ducts stored bile. Perhaps because the gallbladder didn’t. For certain, it’s a congenital defect. (Lazy-Ass Gallbladder.) Remember what Ian Malcolm said in Jurassic Park? “Life uh…finds a way.” Monkey’s body found a way. When his gallbladder malfunctioned, the bile ducts took over. It chose life. I think it does that every day. But we keep an eye on his bile ducts with mini-ultrasounds. The surgery is probably a patch, not a fix. The internist said, “It took him 13 years to get this bad. Maybe it will take 13 years again.” Would I do surgery again? Nope. I would not make Monkeydo live through that twice. The stress took years off my life as well. (Remember, we thought we were simply removing a cyst.)

Monkeydo is 14 now and has great days. Here and there. Other days it’s barf-o-rama around here. I keep a daily journal of what he eats, how he eliminates, when he vomits, and which meds he takes. He’s the perpetual patient. But he seems happy. Monkey always sleeps by me, insists on quality lap time and is very vocal. (He nudges me out of bed by 6:00 am and will bop my head and jump on my back to enforce it.) Yes, we got through it. Monkeydo is a trooper. (That is what they called him at Horizon Vet Specialists.) As for Dr. Holsworth, he remains my hero.

UPDATE: Monkeydo left November 26, 2021. I was heartbroken. He had developed abdominal peritonitis. His internist had no idea why. They suggested exploratory surgery. I said no. I arranged in-home euthanasia. Monkeydo packed light. All his favorite things are still here. Except for my heart. It seems to be missing. That is proof of love.

HE WAS MY LAP CAT

HE WAS MY SLEEPING BUDDY

HE WAS MY FURRY SOULMATE

I MISS HIM BUNCHES.

Related Posts

WE DID IT! GEORGIA IS FREE.

Rescues in the Los Angeles area got 72-hour notices. Georgia was only six but…

April 2, 2024Mittens and Maya: SAVED!

In July 2023, Maya, a Maine Coon mix and Mittens, a tuxedo kitten found themselves…

September 16, 2023